THE DIFFERENT SCALES.

We often need to raise or lower the pitch of a tune to suit the range of individual singers and the Organist has to use some black keys as compensation.

On page 32, we had seen exercises where we used the F sharp and B flat keys, and the singers renamed the notes. In the following exercises, we will use scales which have been moved up or down from its Natural position.

The most common scale we use, is called the Major Scale, and the steps are as selected in the picture of the Chromatic Scale, where the first two steps are a tone apart, followed by a step which is a semitone

apart. Then

3 tones follow in succession and end with a semitone, leading to the

upper pitch of the starting note, which is also called the Key Note, or

the Tonic.

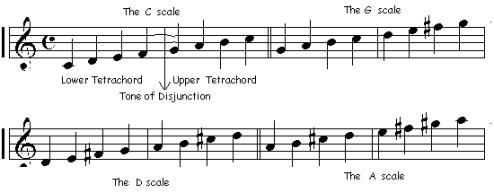

If you examine the scale closely, you will note that the first four notes and the last four notes are mirror copies. They are 2 tones and 1/2 tone and are called Tetrachords. The first four notes are the Lower Tetrachord and the upper four are the Upper Tetrachord. The tone between the two, is called the Tone of Disjunction.

For evaluating the different transposed scales, we make the upper tetrachord of a given scale, as the lower tetrachord of the new one, and the seventh note has to be given a sharp.

Thus, the Upper tetrachord of the Natural (C Scale) is G A B C. The new scale thus starts on G (Key Note), and the upper tetrachord becomes: D E F G. (According to rule, F needs to be sharpened.) Thus we get the 1 sharp scale, which is called the G scale. Generally the sharp is written on the 5th

line immediately after the Clef.

In the above diagram we see that the upper tetrachord of the G scale is D E F# G, and the D scale starts with this as the lower tetrachord, and has A B C# D as the upper tetrachord, and is the he new D scale. Similarly, the next one is the A scale.

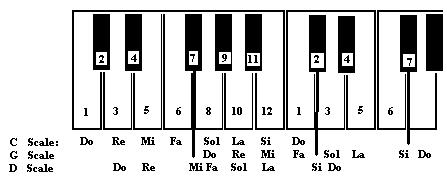

As for the singers, transposition means, moving the Do Re Mi, up or down the sound range. In the case of G scale, they call G as the Do, and rename all the other notes accordingly. In the case of D scale, D becomes Do, etc.

As a general principle, if we raise the pitch upwards by 8 chromatic steps, we always use the step before the 8th step as the note Si. As in the case of G scale, we raised the pitch to G which is step 8 of the chromatic scale, and used step 7 as our Si, which is F sharp. With each rising, we retain the older sharps.

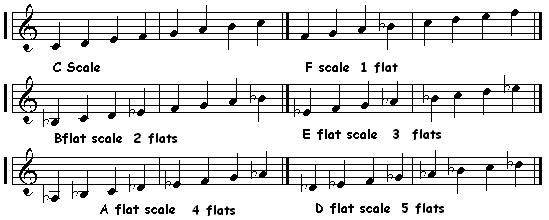

Let us now see what happens if we do the reverse. Instead of taking the upper tetrachord to start a scale, we use the Lower tetrachord as the upper one of a new scale. In this experiment, we will see that we get the flat scales:

C D E F G A B C

F G A B C D E F

Now you notice that the lower tetrachord starting with F has 3 tones. In order to make the third interval a semitone, we can not use A#, as then the interval between G and A# will be more than 1 tone. You have to lower the B by a semitone, and we will get a bonus: we get the Tone of Disjunction..

If we move downwards to the 8th step, we reach F. The first and last notes are having the same name thus we count only the new flat as the additional flat which is the fourth name from the starting name. From F if we move 8 chrromatic.steps downwards, we come to Bflat and the scale starting on this note has Bflat and the new E flat note. In the same way, we have the other flat scales, by moving downwards. Sharp scales are obtained by rising upwards 8 chromatic steps each time. The following table shows the starting note, and the accidentals (Sharp or flats)

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|